Revered as one of the most iconic figures in professional wrestling history, Bobby “The Brain” Heenan is considered by many to be the greatest manager in the history of the sport.. Known for his quick wit, impeccable timing, and unparalleled ability to entertain, Heenan carved out a legendary career as both a manager and a color commentator. His managerial skills shone brightest when he led numerous wrestlers to championship glory, earning him the moniker “The Brain” for his strategic genius. Transitioning seamlessly to broadcasting, Heenan’s razor-sharp humor and insightful commentary became a staple of wrestling television, endearing him to millions of fans worldwide.

Real Name: Raymond Louis Heenan

Stats: 6′ 0″, 224 lbs.

Born: November 1, 1944

Early Life

Bobby “The Brain” Heenan, born Raymond Louis Heenan on November 1, 1944, had an early life that set the stage for his future success in professional wrestling. Growing up in Chicago, Illinois, Heenan’s childhood was marked by modest means and the challenges of urban life.

From a young age, Heenan showed an interest in professional wrestling, a passion ignited by watching wrestling matches on television and attending live events. This early exposure to the sport deeply influenced his aspirations and dreams. The charismatic personalities and the theatricality of wrestling captivated him and left a lasting impression.

Career

Heenan’s journey into wrestling began in the 1960s when he started as a wrestler and later transitioned into managing, a role in which he truly excelled. His early life experiences and his innate understanding of the psychology of entertainment helped propel him to become one of the most memorable and influential figures in professional wrestling history.

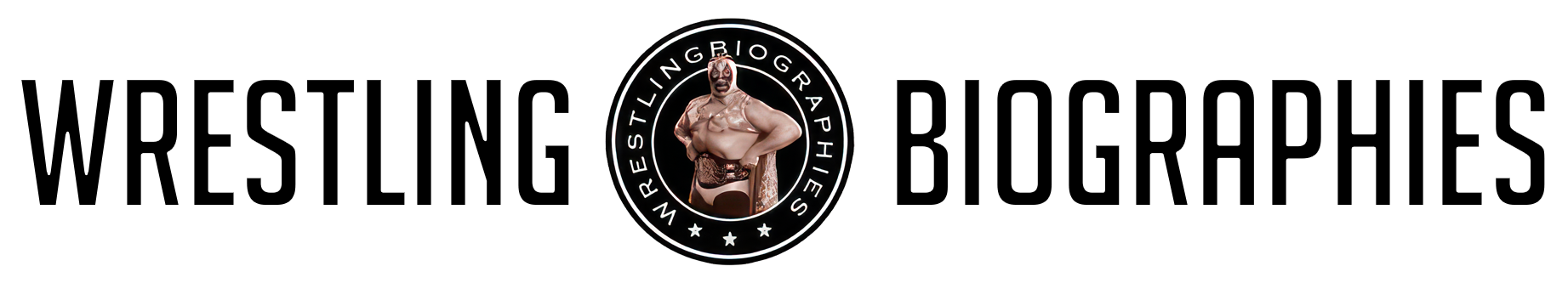

He entered the wrestling business in his early teens, selling refreshments at live events and assisting wrestlers by carrying their jackets and bags. He made his professional debut in Dick the Bruiser’s Indianapolis territory in 1961 at the age of just 17. A natural in the ring who never received formal training, Heenan initially competed as a wrestler and manager under the moniker “Pretty Boy” Bobby Heenan.

At the start of his career, Heenan faced challenges being taken seriously inside the ring due to his lack of physical intimidation, despite his technical prowess. However, after honing his technique in the W.W.A and Central States promotions, the talented Heenan transformed himself into a crafty, tough, and often cowardly wrestler.

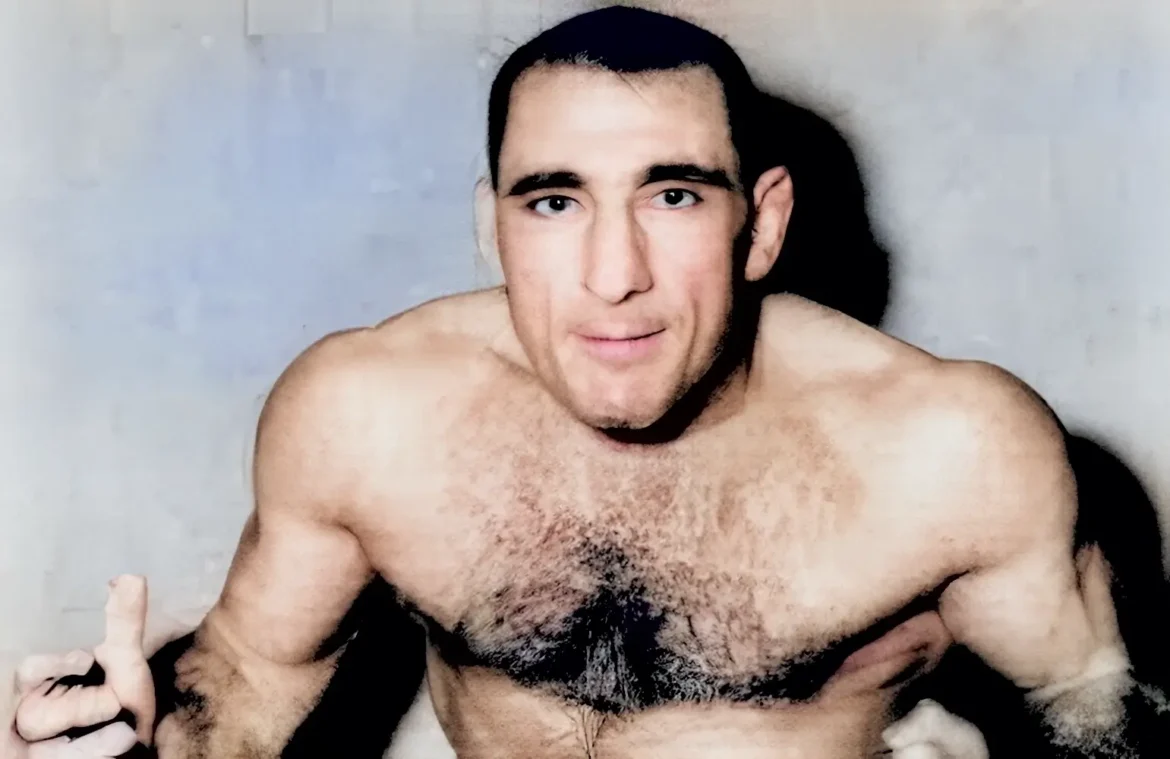

Following a disagreement with Afflis over payments, Heenan left the W.W.A for Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association (AWA), a move that proved highly advantageous for his career. During his tenure as a manager in the AWA, Heenan, who eventually adopted “The Brain” moniker, was paired with some of the AWA’s top rule-breakers. In addition to his valued protégé, Nick Bockwinkel, Heenan lent his wit, humor, and interview skills (as well as frequent outside interference) to villains like The Blackjacks, Ray “The Crippler” Stevens, “Superstar” Billy Graham, Angelo Poffo, Ernie “The Big Cat” Ladd, The Valiant Brothers, Bobby Duncum, Ken Patera, Baron Von Raschke, and many more. Conversely, Heenan’s underhanded tactics placed him in conflict with the AWA’s most popular “good guys,” including heroes like The Bruiser, The Crusher, Billy Robinson, Pepper Gomez, Andre the Giant, Hulk Hogan, and, of course, Verne Gagne. In fact, “The Weasel” shed considerable blood defending his men and their championships.

In 1975, Heenan guided his main protégé, Nick Bockwinkel, to his first AWA World title victory over the long-standing champion Verne Gagne, resulting in a reign for Heenan and Bockwinkel that lasted over five years. “The Brain” also supported “Tricky” Nick when he reclaimed the title in 1980. Moreover, Heenan managed three tag teams (Bockwinkel & Stevens, Lanza & Duncum, and Patterson & Stevens) to six AWA World Tag Team championships, with his iconic team of Bockwinkel & Stevens holding the AWA belts for an impressive total of 27 months.

Heenan’s dominance persisted when he left his long-established base in the AWA and transitioned to the NWA, specifically TBS’s Georgia Championship Wrestling, in 1980. Upon his arrival, AWA protege Blackjack Lanza followed suit and swiftly secured the Georgia TV (forerunner to the WCW World TV) title. Concurrently, The Masked Superstar and “Killer” Karl Kox, new members of the NWA’s Heenan Family, both clinched the esteemed Georgia Heavyweight title under Heenan’s guidance. His rivalries with Wahoo McDaniel, Tommy Rich, and former AWA adversary The Crusher took center stage in the promotion during his time in Georgia.

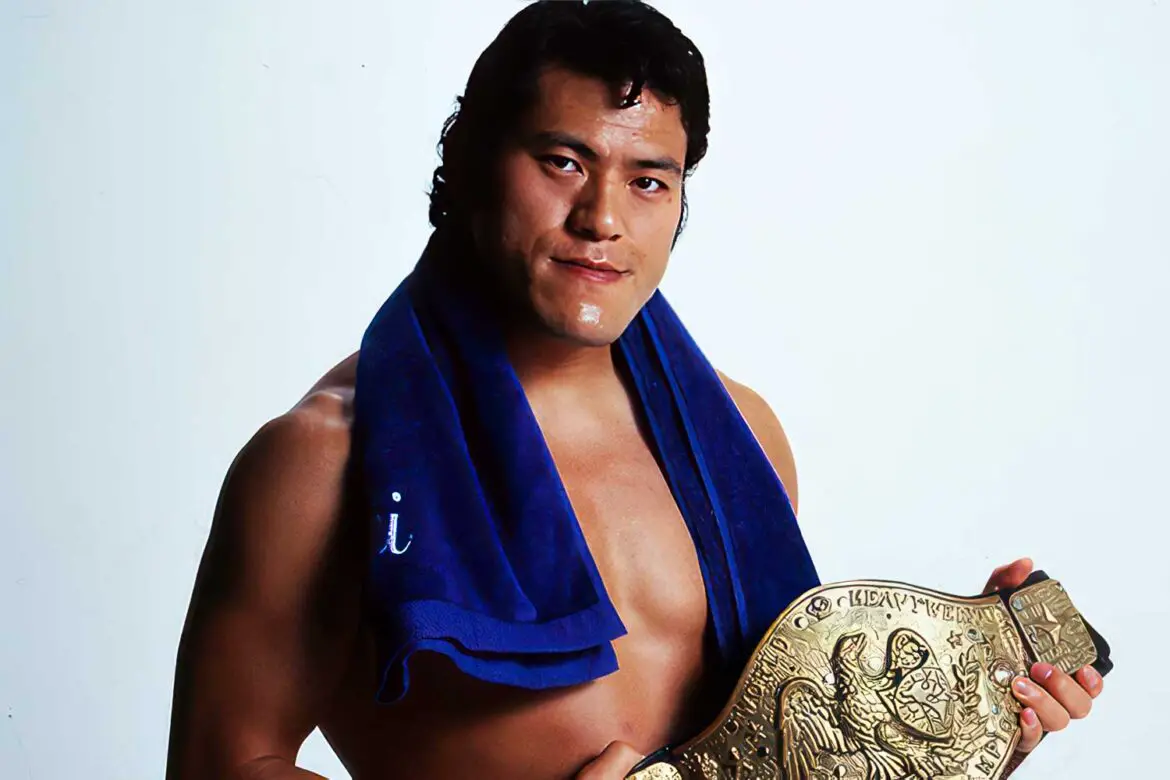

Heenan later departed the NWA and returned to the AWA. His intentions were clear: he aimed to torment anyone obstructing the Heenan Family, particularly AWA icons like Verne Gagne, “Mad Dog” Vachon, and Rick Martel. For around two years, he accomplished just that, guiding Bockwinkel to a series of tainted victories before departing his AWA home base once more in pursuit of new opportunities within the rapidly growing World Wrestling Federation. Upon joining the WWF, Heenan quickly rose to prominence as the top manager, overseeing leading WWF superstars like “Big” John Studd, “Mr. Wonderful” Paul Orndorff, “King” Harley Race, “Ravishing” Rick Rude, Andre the Giant, Mr. Perfect, The Islanders, Hercules, The Brainbusters, and countless other WWF villains in their clashes with Hulk Hogan, The Ultimate Warrior, “Macho Man” Randy Savage, and additional WWF fan favorites. In addition to managing his wrestlers to WWF Intercontinental and World Tag Team titles, Heenan achieved multiple WWF World Heavyweight championships through proteges Andre the Giant and “Nature Boy” Ric Flair.

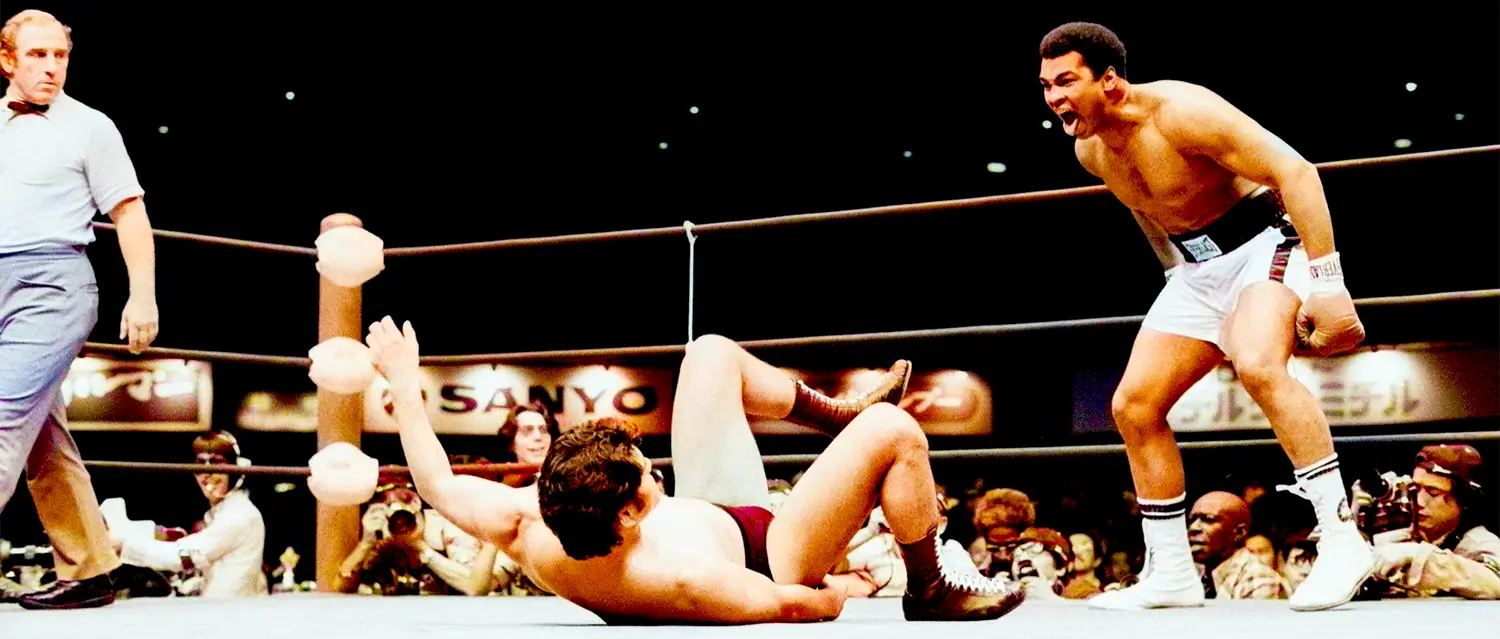

Heenan’s career highlight as a manager came in 1987 when he began managing the legendary Andre the Giant. Andre, a genial babyface throughout the years, took umbrage with Hogan, overshadowing his achievement of being undefeated over the last 15 years. He was scheduled to confront Hogan on an episode of Roffy Piper’s “Piper’s Pit” television segment. When André came out, he was accompanied by Bobby Heenan, who accused Hogan of befriending Andre only so as not to meet him for a title match. While Hogan appeared shocked by Andre’s allegation, Andre doubled down by challenging Hogan for his World Heavyweight Championship belt at WrestleMania III. When Hogan further expressed disbelief, Heenanreveled in satisfaction when Andre ripped off Hogan’s shirt and crucifix. After the buildup to one of the biggest matches in wrestling history (and certainly one of the most viewed and best attended) Heenan saw his meal ticket defeated when Hogan bodyslammed the Giant and pinned him. Heenan and Andre left the ring in disgraced, with Heenan appearing overwhelmed as they were driven away as Hogan played to the crowd.

Heenan with Andre the Giant

Over the following decade, Heenan thrived in the WWF, where “The Brain” became not only the leading manager but also the premier color commentator, or as he called himself, a “broadcast journalist.” His remarkable partnership with Gorilla Monsoon on the USA Network’s Prime Time Wrestling show was notable and highly entertaining. Simultaneously, the WWF’s “King of the One-Liners” became a mainstream celebrity due to his regular appearances on Late Night with David Letterman and The Arsenio Hall Show. Heenan played a significant role in numerous top WWF storylines and was one of Vince McMahon’s most devoted employees off-camera. However, in 1994, a new challenge awaited “The Brain” in his former Atlanta-based NWA territory, now known as WCW. As an announcer, Heenan reached millions of weekly viewers on the highly-rated WCW Monday Nitro, Thunder programs, and pay-per-view broadcasts. However, except for a single WCW pay-per-view appearance as Ric Flair’s mentor, Heenan focused solely on his “broadcast journalist” responsibilities during his six-year tenure in WCW, avoiding any managerial roles.

After half a decade of commentating WCW’s network and pay-per-view events, it became apparent that Heenan’s performance quality was deteriorating. This included his almost revealing Hulk Hogan’s heel turn as a member of the New World Order at the 1996 Bash at the Beach pay-per-view event. He would later admit that he was disenchanted by WCW’s politics and uninspired by its on-screen content. In January 2000, WCW decided to remove Heenan from his Monday Nitro position and the company’s pay-per-view events. He continued to deliver color commentary for TBS’ Thunder program until July 2000, when he was replaced by former wrestler Stevie Ray. Four months later, the decision was made to relieve Heenan from his duties on the syndicated WCW Worldwide series, effectively concluding his six-year affiliation with World Championship Wrestling.

After half a decade of commentating WCW’s network and pay-per-view events, it became apparent that Heenan’s performance quality was deteriorating. This included his almost revealing Hulk Hogan’s heel turn as a member of the New World Order at the 1996 Bash at the Beach pay-per-view event. He would later admit that he was disenchanted by WCW’s politics and uninspired by its on-screen content. In January 2000, WCW decided to remove Heenan from his Monday Nitro position and the company’s pay-per-view events. He continued to deliver color commentary for TBS’ Thunder program until July 2000, when he was replaced by former wrestler Stevie Ray. Four months later, the decision was made to relieve Heenan from his duties on the syndicated WCW Worldwide series, effectively concluding his six-year affiliation with World Championship Wrestling.

After parting ways with WCW in 2000, Heenan occasionally appeared in WWE and had brief tenures in TNA, Ring of Honor, and W.O.W. He also authored two successful books: Bobby The Brain: Wrestling’s Bad Boy Tells All in 2002 and Chair Shots and Other Obstacles: Winning Life’s Wrestling Matches in 2004. However, in January 2002, Heenan stunned the wrestling community by publicly revealing his throat cancer diagnosis. He underwent treatment, and although the cancer went into remission by 2004, he had to endure reconstructive jaw surgery, which temporarily left him unable to speak. His health challenges persisted, and between 2010 and 2016, Heenan experienced several falls that led to a broken hip, shoulder, and pelvis.

Awards & Honors

In 2004, Bobby Heenan received the Cauliflower Alley Club’s “Iron” Mike Mazurki Award. He is also an inductee into the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the WWE Hall of Fame (2004), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum (2006), and the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2010).

Death

Ray “Bobby” Heenan passed away on September 17, 2017, at the age of 72, due to organ failure caused by throat cancer. This illness significantly affected his voice, a tool central to his success as one of the greatest managers and commentators in wrestling history.

Heenan was honored with a special video package on “Monday Night Raw,” highlighting his legendary career and memorable moments. WWE also posted a tribute on their website and social media platforms. He was further lauded by wrestlers and other members of the wrestling community and fans worldwide.

Legacy

Bobby, “The Brain” Heenan’s professional wrestling legacy is profound and multifaceted, cementing him as one of the industry’s most iconic figures. Renowned for his exceptional wit, charismatic persona, and unparalleled skills on the microphone, Heenan redefined the role of a wrestling manager and commentator. His ability to blend humor, intelligence, and a keen understanding of in-ring psychology made him a beloved and influential character as a heel manager and color commentator. He managed some of the biggest names in wrestling, leading them to championship glory and becoming an integral part of their storylines. As a commentator, his insightful and often humorous observations added significant entertainment to wrestling broadcasts, endearing him to fans worldwide. Heenan’s influence transcends his on-screen roles, inspiring generations of wrestlers, managers, and commentators with his innovative character development and storytelling approach. Even after his passing, “The Brain” continues to be celebrated for his contributions to the art of wrestling entertainment, remembered fondly by fans and peers alike as a true legend of the sport.

Resources

Wikipedia: “Bobby Heenan.” – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobby_Heenan

Sportscasting.com Editors. “The Heartbreaking Demise and Death of Legendary WWE Manager Bobby ‘The Brain’ Heenan.” – www.sportscasting.com

WWE.com. “Bobby Heenan.” –www.wwe.com

Sportscasting.com. “NBA Basketball Legends, Current Superstars, Team Breakdowns.” –www.sportscasting.com

YouTube. “Sportscasting.” – www.youtube.com/channel/UCqNJKuz5yhk6Ct2ah22Ny6A

Frequently Asked Questions

Bobby “The Brain” Heenan, born Raymond Louis Heenan, was a legendary figure in professional wrestling, known for his roles as a manager, color commentator, and occasional wrestler. He is celebrated for his quick wit, humor, and intelligence, which earned him the nickname “The Brain.”

Heenan began his career in the wrestling world in the early 1960s. He initially started as a wrestler but gained immense popularity and acclaim as a manager, where he showcased his strategic mind and charismatic persona, leading numerous wrestlers to success.

Heenan’s unique blend of humor, intelligence, and an innate understanding of wrestling psychology set him apart. His ability to play the role of a heel manager to perfection, along with his exceptional skills on the microphone, made him one of the most entertaining and beloved personalities in wrestling history.

Throughout his career, Heenan managed several high-profile wrestlers and was instrumental in their successes. As a color commentator, his insights, humor, and chemistry with fellow commentators added a significant layer of entertainment to wrestling broadcasts. Heenan is also remembered for his involvement in classic wrestling storylines and feuds.

Bobby Heenan’s legacy in professional wrestling is marked by his contributions to the entertainment aspect of the sport. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest managers and color commentators in wrestling history. His influence extends beyond his on-screen roles, having inspired future generations of wrestlers, managers, and commentators with his innovative approach to character development and storytelling in the wrestling world.

Death

Death